SMALL BUT MIGHTY

From shrimps to spiders, capturing the natural world’s smaller inhabitants calls for specialist kit and knowledge.

Macro cinematography demands meticulous control, with a mix of studio-based and on-location work. Veteran filmmaker Richard Kirby says most macro cinematographers build a simple set “and take that anywhere,” blending the back of the set and the background by incorporating local elements like branches.

Katie Mayhew, whose macro work for the BBC’s Wild Isles was all filmed in the wild, says a controlled set on location, “lets you work with the right materials and the right plants, while the humidity and temperature control is correct for the species you’re filming”.

“If you’re using a longer lens, you might want to bring in some sort of out-of-focus foliage or sticks in the foreground,” says Owen Carter, who specialises in macro camera operating. “That just makes it feel a bit more immersive when you’re filming smaller animals.”

The environments through which the animals and insects move can also be adjusted to make the routes more conducive to filming – Kirby talks about laying a stick onto his set for a line of army ants to follow, while Carter says a tweak of the right leaf can get creatures to follow a path of your choosing, “so when you are programming a motion control move, it will follow that path”.

Mayhew says Canon and ARRI 100mm macro lenses are popular. Probe lenses, such as Laowa have fans too.

“With a probe lens, because it’s effectively on the end of a stick, you can track and pan with it, or do [macro] crane shots,” says Kirby.

However, such lenses are also prone to vibration. “When you’re filming something so tiny, any vibration on the lens, including the heartbeat going through your fingertips, will make your image move,” says Mayhew. “I tend to use remote follow focus and then all my focusing is done through a monitor.”

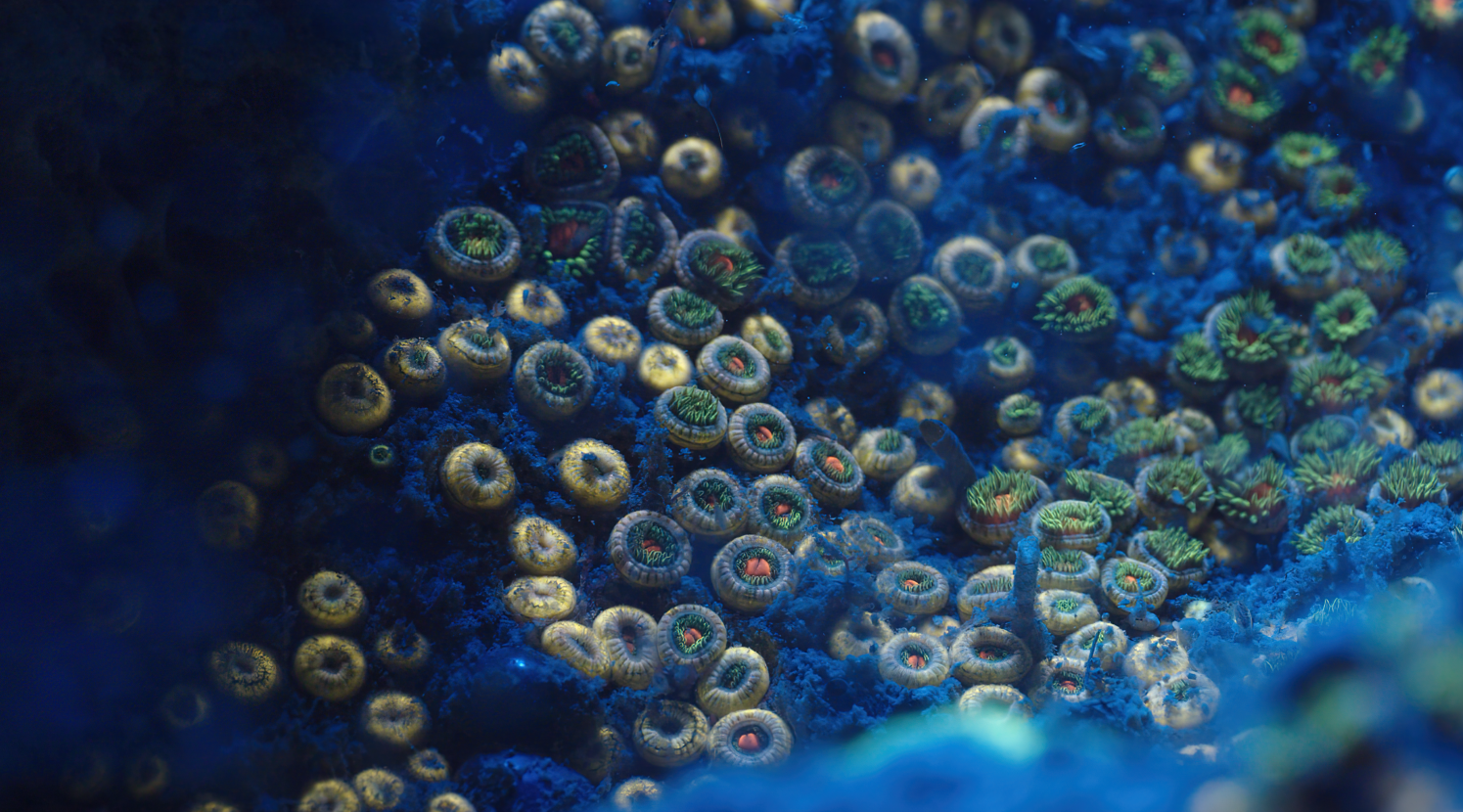

To shoot Red Sea corals in time-lapse, DP/producer/director Jean-Charles Granjon set up an underwater studio and rig, filming on RED cameras with the Laowa 24mm 2X Macro Probe Lens. “The wide angle gives more of an idea of the environment,” he says. “With a maximum aperture of F14, it provides quite a narrow depth of field if you are 1cm from your subject.”

“It’s a very dynamic environment where every vibration – even just breathing – can be transferred to the equipment,” he explains. “Underwater macro cinematography is like stepping inside an Alice in Wonderland world. Everything changes.”

“For large sets, I use ARRI SkyPanels as the key light, then spot light, using Dedo lights with focusing lenses and gobos,” says Kirby. “These are great at creating various degrees of ‘dapple’ in a very small area. If you want quite a dark frame, a fibre optic is great for putting little pools of lights in the background. If you’re building a burrow sequence, Lume Cubes work well for getting light on the animal. You just put a diffuser on, and you get a very soft underground light, with lots of dark areas as well.”

Keeping focus at the macro scale means thinking differently. Mayhew uses extension tubes, which allow you to move the camera glass further away from the sensor, so magnifying the image. “As you do that, you do lose light, but you can focus closer to your subject than the lens would normally allow.”

Mohan Sandhu has developed kit tailored for natural history filmmaking. “I’ve got a 6-axis interface at my fingertips, my left hand is controlling X, Y, and Z, and my right hand is controlling pan, tilt and focus. I can move the camera forward and back, move the focus forward and back, or a combination of two.

“For more extreme macro I won’t be focusing, I’ll just be using the plane of focus as a target. You’ve got a tiny depth field with a tiny subject, but you just try to end up in tune with the subject, sense its movement, and keep that peaking plane of focus exactly where you want it to be.”

Getting the subject in the frame, in focus with shallow depth of field, or getting behaviour that the script requires, takes a great deal of patience. “It’s best to work on the close wide contextual shot first, then move on to the close-up cutaway,” says Kirby.

To help, invertebrate/animal wranglers can introduce captive-bred specimens into a macro set. “We had a wrangler position a male spider in the right spot and then bring in females to get its attention,” says Sandhu. “It’s like blocking when you work with an actor, but with a depth of field of less than a millimetre; you’ve got to be bang on to get the shot.”

–

Words: Michael Burns