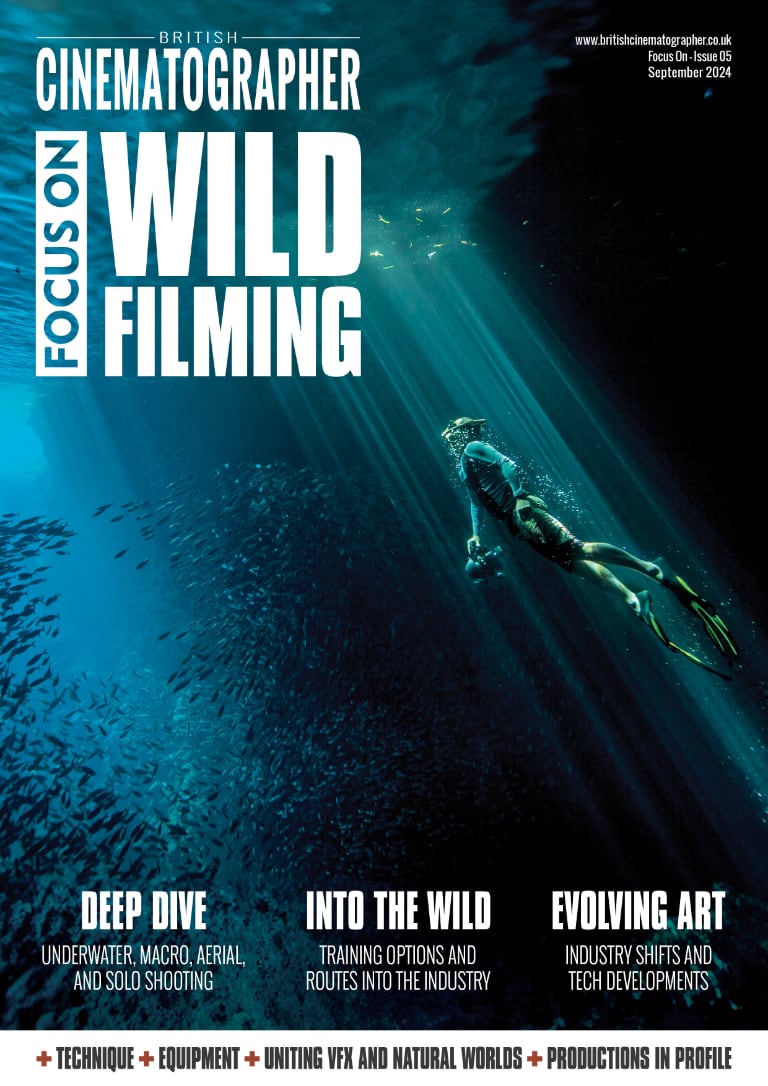

A wildlife cinematographer doesn’t only capture the results of evolution in the natural world – they also experience it in the very tool boxes they take into the wild: Shifts from film to digits, terrestrial radio to satellite phones, paper maps to GPS systems, and more.

None of that means it’s necessarily easier to grab extensive footage of, say, snow leopards or wolverines than before, but certainly to be a wildlife DP now – ironically, in an age where wilderness is more imperiled than ever before – is to have an array of new tools at your (perhaps sun-cracked or frostbitten) fingertips, starting with the camera and glass in their grip.

Ester de Roij, both a veteran researcher and cinematographer, uses a range of cameras, such as ARRI Amiras, Sony Venices, RED Heliums and Geminis, and more, on projects like Frozen Planet and Welcome to Earth (among numerous credits). She agrees there’s “been a huge change in technology in the 11 years I’ve been in the industry” though with that, the “increased demand on the quality and look of our sequences has meant more kit on shoots, and more pressure on where we film and what we film.”

Previously, the go-to on long-lens sequences for capturing wildlife in situ, and relatively undisturbed, was Canon’s HJ18, “which with an extender had a much longer reach and was much lighter to carry.” But for most of her years literally in the field, the default has been Canon’s CN20 – with its 20x zoom, which turns out to be “much bigger, bulkier – and sharper. But you need to get a bit closer to your subject to get the same shot sizes.” As for overhead and terrain-establishing scenes, “drones are thrown at every shoot and are still primarily used for scenics, although I guess it’s relatively cheaper and easier than using a helicopter.”

Recent advancements in camera movement technology are addressing limitations of traditional long-lens setups. AGITO’s ability to support large camera payloads (up to 150kg) means you can use long lenses dynamically, much like a tripod on wheels. Rob Drewett, cinematographer and co-founder of Motion Impossible explains, “While you could strap a 6-axis gimbal onto a 4×4 to bring immersive tracking to your shots, it has limitations. It’s noisy, you can’t reposition quickly, and it affects wildlife behaviour. AGITO’s agility, speed and capacity for various camera setups provides a better solution for dynamic long-lens work.” Additionally, being remote controlled, AGITO can access places humans can’t or shouldn’t go, allowing for flexible shots without disturbing the wildlife. “When filming wild dogs for Predators, we could quickly capture the action [pack hunting] with a wide range of camera angles. Any other tool would have meant missing the opportunity.”

David Baillie oversees Wildcat Films, a production company whose motto is “challenging stories for challenging places”. To document some of those challenges, he calls the CN20 “almost more revolutionary in the genre than the expanding range of digital sensors” and also allows that since he “began natural history filming with WW2 16mm cameras fixed with Meccano to school microscopes in the ‘60s, I can safely say I’ve seen quite a change in the tool box!” But he adds that when filming “natural history, the tool box is only as good as where you can take it. And no amount of technical wizardry can make up for field work and an understanding of the natural world at the other end of the lens.” Those intuitive knacks, he says are usually “something you are probably born with or at least stems from a childhood steeped in exploring the natural world”. (And which we explore elsewhere in this issue in our “Pathways” article.)

But in addition to new gear, Baillie thinks there’s room for new approaches, too: “I’ve worked and still work across many genres, including current affairs, commercials and drama. As a result I often find the insular nature of natural history production immensely frustrating. Sometimes I feel [those] producers should be made to spend a week observing an episodic drama shoot or a commercial just to open their eyes to other ways of making movies. For so long, natural history has effectively been filmed the same way – in 16:9, usually on a compressed RED sensor, with the ubiquitous CN20. Wildlife does often require long lens work, but I believe that there is also a role for the storytelling techniques we use in drama.”

He notes than an “ARRI sensor can be graded for dramatic effect,” though the RED cameras used by the BBC – which, along with Netflix and National Geographic, accounts for the bulk of current wildlife documentary production (with Apple TV+ throwing its own hat in the ring) – have advantages “such as a preroll and higher resolution that allow for reframing in post.” But Baillie laments that “unlike drama, the DP has no input to the grade, if there even is a grade,” and wonders whether the BBC, in “cling(ing) to its old school attachment to 16:9 […] misses out on the storytelling opportunity for using a widescreen format such as 2.4:1.”

Remote stays

Widescreen-filling vistas are one of the specialities of Ivo Nörenberg, the Norwegian-based cinematographer whose credits include White Wolves: Ghosts of the Arctic, A Perfect Planet, and the can’t-argue-with-the-title Amerikas beste Idee: 150 Jahre Nationalparks in den USA.

We caught up with him after he’d just returned home from another far-flung locale, a process he describes as flying “to the capital airport, (then) you are picked up by the bus, you go to the port, you take a boat to the island, and that’s it. After one month, you go back home.” Remote stays which sometimes indemnify filmmakers if the host country is undergoing any roiling politics back at the capital.

He reminded us that in addition to the cameras one holds or stalks with, wildlife cinematography often requires automated remote cameras too – the better to capture that elusive charismatic megafauna, with no humans around.

Nörenberg also uses a gamut of cameras. Alongside his own affinity for ARRIs, he, too, will wield a RED when working for the BBC. But for remote work, he’s “really a fan of the Sony F6. It’s just so easy to control it […] and it’s very good on batteries.” And if you have to replace it because “a bear decides to eat it – it’s not as expensive.”

But it’s not only a matter of packing in cameras, snackable or otherwise, to far-flung locations. “You (still) need food, water (and) clothes,” to sustain you for weeks at a time. It also helps to know all the basics of first aid, and “if there is no cellphone connection, we have a satellite (phone) for safety.”

One might also think that when shooting digitally, in addition to no longer having to carry extra film canisters in your seaplane or Land Rover, that with a satellite phone link, one could feed data back to the “mother ship” – whether in Bristol, Hollywood, or anywhere else – in more or less real time.

But Nörenberg notes, “there’s so much data, it’s impossible to load.” Everything is “backed up on SSDs and hard drives.” And those – like the cameras themselves – require power. Might that be solar now, to minimise impacts on the very Earth the documentaries are imploring us to save?

Alas. Nörenberg says that “the problem is the solar panel systems, (the ones that) have enough power, they are so heavy, you mostly can’t transport them.” They are not, he says, “environmentally friendly”, owing to being “huge and heavy. Gasoline is still the most efficient way to transport energy. Unfortunately.”

And if we can’t even wean ourselves from gasoline, what are our prospects for dealing with other fast-arriving aspects of the future, like AI?

Katie Wardle, who describes herself on social media as not only a wildlife camerawoman, but a “long lenser” – and whose credits include National Geographic’s Welcome to Earth, and underwater work on A Year on Planet Earth – says “I think there’s nervousness surrounding the way technology has progressed when it comes to AI, etc.,” but she also doesn’t think “we have much to worry about. […] The beauty of wildlife stills and film is that it’s authentically true to the moment; the awe of the images comes from the fact it seems unreal to have been captured. To get an image of a very rare animal, in nice light, in perfect composition doing a behaviour never seen before. I don’t think you can recreate that digitally because the reason it’s special is because of the moment and skill of the person.” In addition to that rather wondrous non-human in front of the lens.

But she also allows that there’s been an increase in “VFX in wildlife series and it’s hit and miss with the audience. In some instances it’s really exciting (and) we can get more creative on location with transitions and storytelling techniques.” Other times, though, it “feels less authentic. The new dinosaur series are huge feats and it’s exciting to see stories of creatures that are historic or mythical […] But I think it fills a different space in entertainment to normal observational documentaries.”

More importantly, Wardle stresses that “we are in the middle of a biodiversity crisis along with every other major social and environmental crisis happening. I think our shows have a responsibility to document what ‘ephemeral nature’ we have left and I think the audience needs it as a reminder that there’s so much beauty left [worth] fighting for on this planet. No digital copy can translate the same peace and wonder that the real tangible natural world can.”

A delicate balance

Brian Henderson is the founder of Wildmotion, a group that “represent(s) the entire ecosystem of filmmaking in the natural world”, as their website states, seeking to partner with wildlife filmmakers everywhere, getting them the tools and support they need. He’s also the executive producer of the Hollywood Climate Summit Film and Television Marketplace, and thinks there may be a kind of Goldilocks zone for wildlife filmmaking. On the one hand, “if they get too serious, they turn people off – but if they’re too shallow, they’re not doing anything. Most nature films try to lure you into watching with beauty,” he says. Then come “the zingers”.

Among those zingers, one involves “humpback whales in an Indian Ocean where so much of their food supply has been depleted that they are reduced to floating on their backs – rather than burning energy in pursuit of calories – hoping fish will jump in.”

He also cites an Antarctica that’s getting more rain than snow, as the planet warms. When that rain freezes, it also freezes young penguins whose bodies aren’t adapted for ice. But “no one will watch dead baby penguins.”

Henderson also agrees there may be a role for VFX, especially as more species follow those aforementioned dinosaurs to extinction: “Now technology is readily available – to tell stories of things we can’t see anymore, because animals have died off. Stories about things we’ve lost so we don’t lose more.” That’s also why he thinks it’s important to “continue to shoot in the highest resolution,” and a reason for “shooting in 8K now; future proofing is going to be a thing.”

Thereby keeping the imagery alive, at least; a survey of how things really were (and potentially, how they might be again), available for viewers who are “maybe two generations behind us – young people who don’t have to be convinced of this issue. Their stories won’t have to convince audiences that they have to care.”

Though Simon de Glanville, an Emmy nominee for Super/Natural and Forces of Nature, with numerous other credits and film festival wins, wonders if it might be possible to make the images look too pretty: “I do worry sometimes that in our quest to always make images as beautiful and pristine as possible, we can unwittingly generate a sense of complacency in the audience […] So often, in pursuit of these pristine images, we are framing out the human activity that is actually present in so many of these places and I worry that we are doing the audience, and the planet, a disservice by perpetuating the reassuring sense that this untouched natural world still exists.”

Alaska-born Erin Ranney, whose work includes PBS’ Nature, and NatGeo’s Queens series, about matriarchal societies in the wild, actually wrote to us from a remote island (though on the topic of evolution, it was unclear whether it was the Galapagos), via what was described as “a highly expensive WiFi hookup,” and observes that in her “time filming so far, I’ve experienced droughts, hottest seasons in recent history, mass die-offs of wildlife multiple times and animals struggling to adapt to new patterns and systems. It can be really scary to see the consequences of our actions.”

So the evolution isn’t simply one of technology, such as being able to capture night scenes more vividly, or plant a camera in ever remote locations, but one of intent, too: Perhaps reminding viewers – now and future – of those words of B. Traven, the mysterious author of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, who may have disappeared into the mountains himself: “This is the real world, muchachos. And we are all in it.”

–

Words: Mark London Williams