"Every story has its own language"

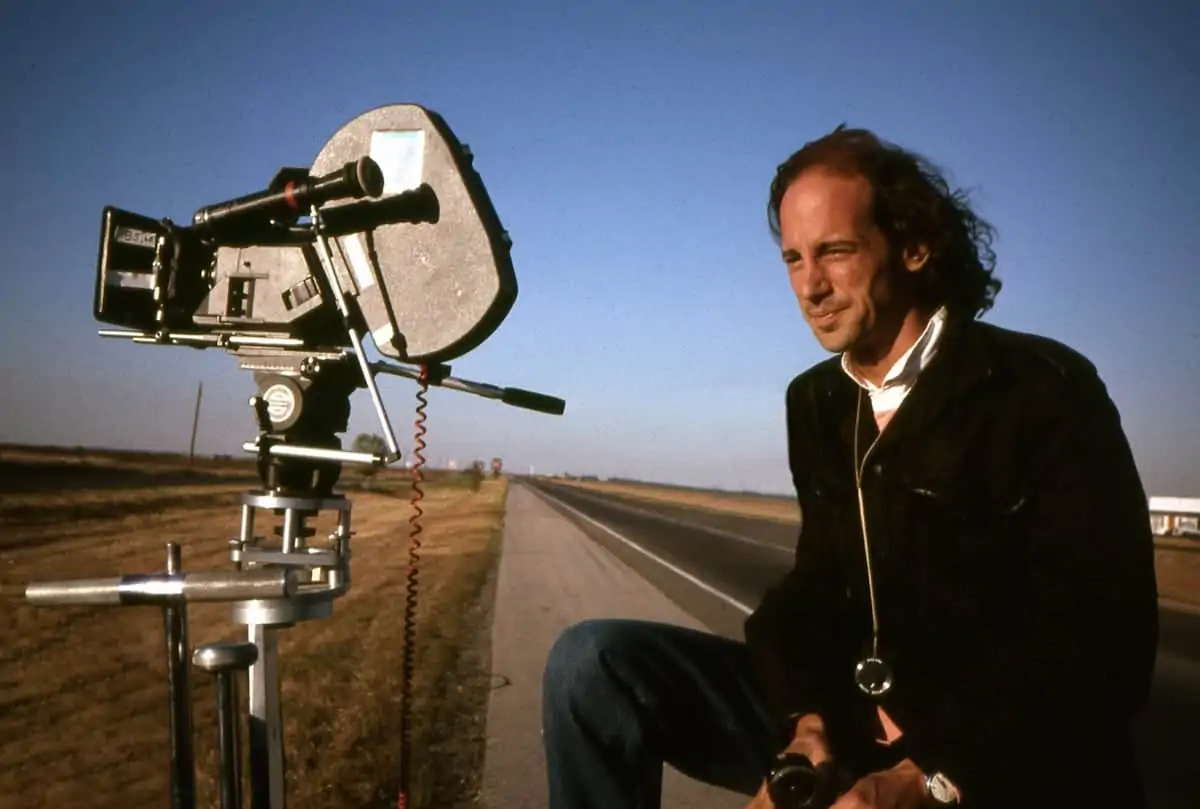

Ed Lachman ASC

"Every story has its own language"

Ed Lachman ASC

Lead Image: Credit - Mary Cybulski

BY: Birgit Heidsiek

As a Director of Photography who worked with some of the most prominent German New Wave filmmakers, as well as with the most influential American independents, Ed Lachman finds for each story its own cinematic language. On the occasion of the 71st Cannes Film Festival, he was awarded the 'Pierre Angénieux ExcelLens in Cinematography'. Birgit Heidsiek spoke with him about his preferred projects, paintings and perspectives.

As the son of an exhibitor, you grew up with motion pictures. What impact did that have on you?

I was in art school. I was studying art history and visual arts to be a painter. When I attended an appreciation course on cinema at Harvard, I saw the Italian neo-realistic film Umberto D by Vittorio De Sica. It was constructed primarily with images and it used very little dialogue. I got excited about the idea of creating a story with moving images. So when I picked up a camera it was easier to create images through a lens than being in front of a blank canvas. That was really my initiation into cinema.

Another real influence for me was Robert Frank’s book “The Americans”. I was taken by the idea that you could instill in a photograph your own subjectivity, your own poetics - a documentation of the world around you. So those were really my beginnings.

I gravitated towards documentaries because that was a way to enter into production and films that I was interested in when I began.

I worked with the Maysles Brothers for a number of years. They had done Salesman, Gimme Shelter and later Gray Gardens. I did sound and second camera for Al Maysles who was the cinematographer. That became a formidable film school for me.

How did you come to work with Werner Herzog and the German New Wave?

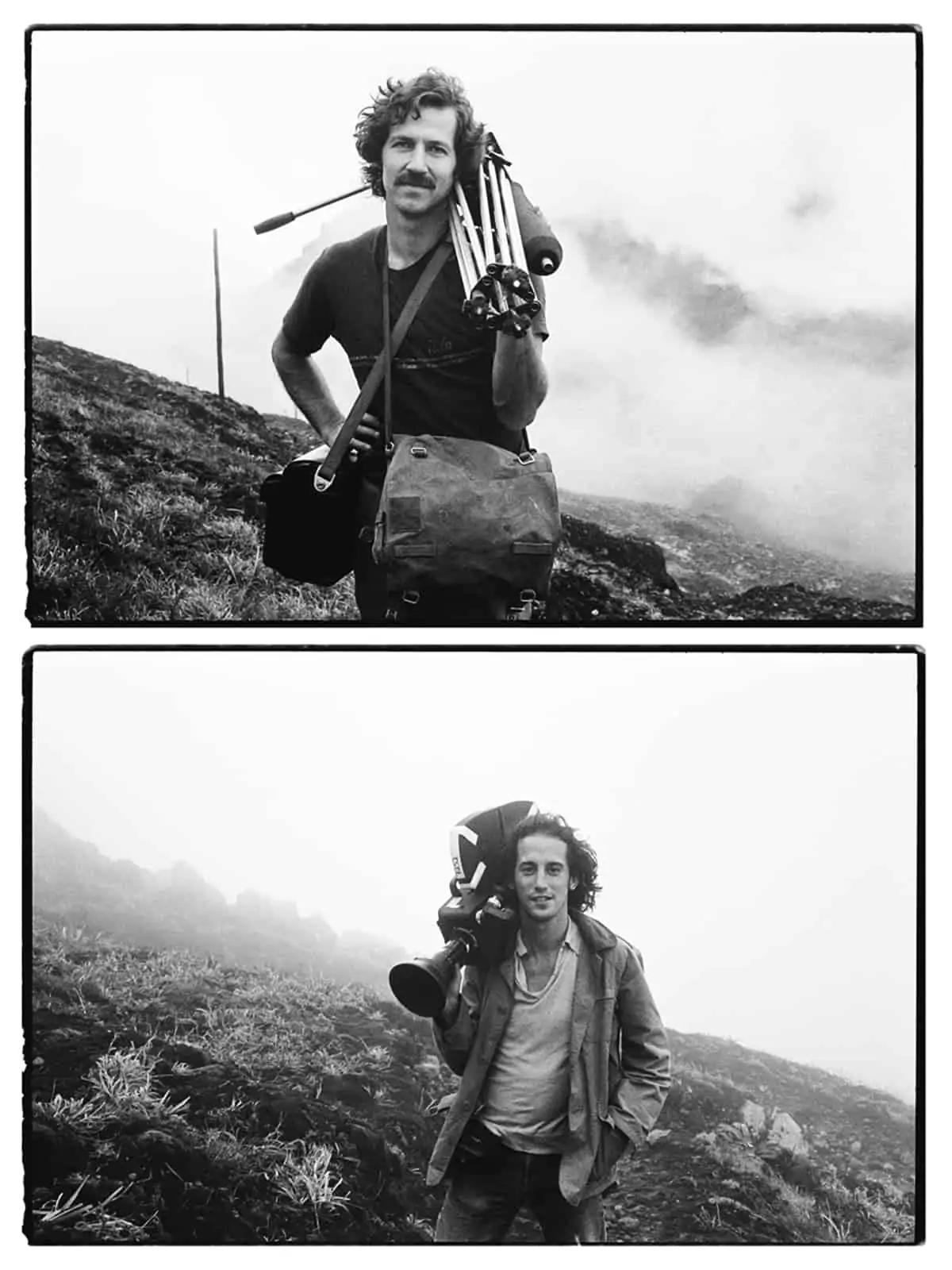

I had the good fortune to work with Robby Müller, the Dutch cinematographer and the director Wim Wenders. I had seen Alice in the Cities by Wim and became enamored by it and became friends with him, so when he came to America to shoot The American Friend, I worked with Robby on it. I was this oddity, the American friend through meeting Werner Herzog in Berlin when he showed one of his earliest films, Signs of Life. The first film I worked with Werner was La Soufrière. He called me at five in the morning to come to this island in the Caribbean, Guadeloupe, where there was going to be a volcanic eruption. He said he was going to face God and country. Was I willing to come? And I said: ”What film stock are we gonna shoot?” because back then it was 16mm. When I got there, I waited three days for this crazy German guy to arrive, and sure enough he arrived with Jörg Schmidt- Reitwein and we made this film La Soufrière - thank God it didn’t erupt. Then we worked together on Stroszek and I did other smaller films with them like Huie’s Sermon and How Much Wood Could a Woodchuck Chuck?

After Werner and Wim, I worked on a small project with Fassbinder, The Last Train to Harrisburg or The Blue Train, and following that with Volker Schlöndorff on A Gathering of Old Men. Basically, I worked with many of the German directors when they shot in America.

Do you have a special affinity to German culture?

I was influenced by German culture because in art school my main interest was German Expressionism. So it was a natural progression from my understanding of German Culture through German Expressionism and the painters that came out of that movement like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde and others like Otto Dix to an interest in the cinema of Germany that was reuniting culturally with the rest of the world in the Seventies because they were supporting the young filmmakers like Alexander Kluge, Reinhard Hauff, Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders, Volker Schlöndorff and Fassbinder. I even lived in Munich for a while in the Schwabing Scene. I guess I’ve always had a connection to Germany and its culture.

How did you meet Ulrich Seidl?

When Werner saw the film Ken Park that I had co-directed with Larry Clarke at Telluride Film Festival in 2002, he came out and he said “not bad - but that’s kids' stuff compared to Ulrich Seidl, a director from Vienna”. So I thought, “Wow! Who’s Ulrich Seidl?” That year I was invited to the Viennale where I had a retrospective. The director Hans Hurch showed me Ulrich Seidl’s earlier films like Losses To Be Expected and Hundstage. I was so taken by them and Ulrich offered to meet me. When we met again a month later at the International Documentary Film Festival (IDFA) in Amsterdam, I said yes right away to his invitation to work on Import/Export. After that project, we worked together on the Paradise Trilogy, Faith, Hope and Love with his exceptionally talented Austrian cinematographer Wolfgang Thaler (I always thought they didn’t really need me, but again, I was there as the American friend, who respected and loved working with them).

So it wasn’t so much An American in Paris, as it was An American in Munich or Vienna! You also worked on many independent American cult films. Is there more room for creativity on indie films?

Honestly, I was always interested in the Independent Film Movement. I was always interested in personal visions. Actually, I learned about American Cinema through Europe in a strange way because of my roots and background in the art world. I always considered Film to be an art form more than a commercial entity. So I sought out the people that had individual voices in their storytelling who were more interested in personal stories, character-driven stories.... There is a part of commercial filmmaking - and I don’t mean to be pejorative about Hollywood because Hollywood doesn’t only make these kind of films, but they certainly make a majority of them - which is driven by, I call it video games and amusement rides. I’m not interested in special effects and the size of my crew, or how many lights are being used. The smaller the crew, the more intimate the story can be. That’s what I’ve always have been interested in. Also, as far as my own work is concerned, I’ve done installations, photography and artwork that have been shown in museums. I am in the collection of the Whitney Museum and the Museum of Modern Art. I’ve had a show at the Ludwig Museum in Cologne through the Filmkunst Festival. Now I’m doing even more of my own personal photography and installations. I did an installation of a Hopper painting at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid. The Hopper Retrospective travelled from Spain to Paris.

I am interested in images, not only cinematic images in films, but cinematic images in other mediums and forms.

"I realized that painters came from different personal, social, and political positions - why they paint and how they painted. So I thought you can do that in film, too. The important thing is the ideas behind the images, rather than making them into only an aesthetically beautiful construction."

- Ed Lachman ASC

How do you describe your visual style?

I feel every story has to find its own semantics, its own language. I don’t feel as though I have to have a visual signature. I don’t think every story should be told the same way. In fact, that’s what I like about my work, exploring different ways of telling stories with images.

I realized that painters came from different personal, social, and political positions - why they paint and how they painted. So I thought you can do that in film, too. The important thing is the ideas behind the images, rather than making them into only an aesthetically beautiful construction.

How does this turn out when you work with a director like Todd Haynes?

Todd’s brilliant at approaching each film in the language that he finds necessitates the story. The interesting thing about Todd, is he isn’t just representing images, but using them as metaphors. We worked on films set in the Twenties, Thirties, Forties and Fifties, and in the Seventies! If you look at his films from Far From Heaven to Wonderstruck - one finds the narrative component in the image and the image in the narrative with his ability to transport the viewer into different eras of the past, while making you feel like the events of the characters are happening in front of you now.

In Wonderstruck, we were creating visual metaphors for deafness. It was a film about hearing with your eyes. Wonderstruck was a combination of the gritty street look of the Seventies, with the raw camera movement and naturalistic lighting contrasted to the black and white studio chiaroscuro lighting and balanced formalism and orchestrated camera movement of the silent movies of the Twenties. We were mirroring the deafness of a young girl as she was growing up - her mother was a silent movie actress - so what better way to show that world than to show it through the cinema of the silent period which also mirrored her own deafness.

How do you develop the visual concept with him?

Todd always likes to create a look book that gives all the departments and myself his initial ideas - illustrating his ideas through the politics, the history, the demographics, the art, and the fashion and cinematic language of the film’s time period. That creates the emotional structure of the film for me. In Carol, we situated the structure of the subjective viewpoint of the characters falling in love by shooting through framing devices like doors, windows, cars and closures. Textures of rain, reflections, the weather, even the film grain of Super 16mm - an obstructed, hindered and inhibited view (for us the viewers) of forces around the characters in their emotional isolation. Something seen, but hidden. A way of externalizing or visualizing what’s inside the characters and the subjectivity of the gestures of falling in love. That’s possibly why the film reaches people. Not just because it’s a story about two women falling in love, but the actual act of falling in love that we can all relate to, where you’re reading every sign and meaning between them. So it’s not just the representational world but a psychological/mores subjectivity of the characters about the isolation of desire and romantic imagination. The unsettling of the amor is mine. They’re entrapped by their own views outward as we’re looking in on them through car windows, diners, apartments, doorways. Splattered rain drops and street reflections and streets in winter weather.

What kind of look did you create to reflect the period?

With Carol, we were creating a stark, lived-in reality, a lived-in period reality rather than a stylized cinematic reality - rather than a picture-postcard manufactured cinematic world. So we weren’t going for a noir or melodrama of Far From Heaven, Douglas Sirk look of the late Fifties, but a quieter documented austere world of photo-journalist photography of the time. In America after the war, the infrastructure wasn’t physically destroyed like Europe but, there was an austere, almost grey look in the cities at that time and it fit the emotional make-up of the characters who couldn’t really act on their own inhibitions about their own sexuality and needs. It came out of Patricia Highsmith’s 1952 book, The Taste of Salt.

We also referenced the photographer Saul Leiter who was a street photographer in the ‘50s who used his images more like an abstract expressionist in mood and feeling, than in its content.

Director Todd Haynes, Gaffer John DeBlau. Credit: Wilson Webb

"As I got older with more experience, I learned that there’s more than one way to solve a problem creatively. The important thing is that we look inside and outside ourselves with new eyes."

- Ed Lachman ASC

Does it depend on the project whether you choose to shoot on film or digital?

I’m seventy-two years old, and since I grew up experiencing and seeing film through a negative, I have a prepossession for film because I have an affinity to the photographic image in its depth and color. I like to think of it this way: Artists use different mediums and different techniques to create different looks. So, for me, the look of the digital world is a kind of photorealistic look. If I am doing something more impressionistic, I want to use film because there is a certain distance the viewer has to the image. We shouldn’t limit our visual ability in our storytelling with only a single palette or technical means.

What is the reason for the resurgence of film?

The technical apparatus of constructing images is being driven by the market place, HDR, more K, 4K, 6K, 8K. If you look at what cinematographers are trying to do, they are trying to get away from that. They’re using lenses from fifty years ago, rehousing Cooke Speed Panchro, K35s, and Kowa lenses. As we speak, I’m rehousing my set of K35s. They were the first lenses I had when I bought a Moviecam years ago. So we’re going in the opposite direction than the industry is pushing us through marketing. I always say this in a funny way. They always say they want to make the digital world look like film, but I never hear anybody say they want to make film look more digital. There is a reason why.

I know digital is here to stay - “whatever”. Steven Soderbergh just did a film with his iPhone and it worked for the story, and there was the wonderful film Tangerine directed by Sean Baker in 2015.

I think the content has to drive the technique’s style of the film.

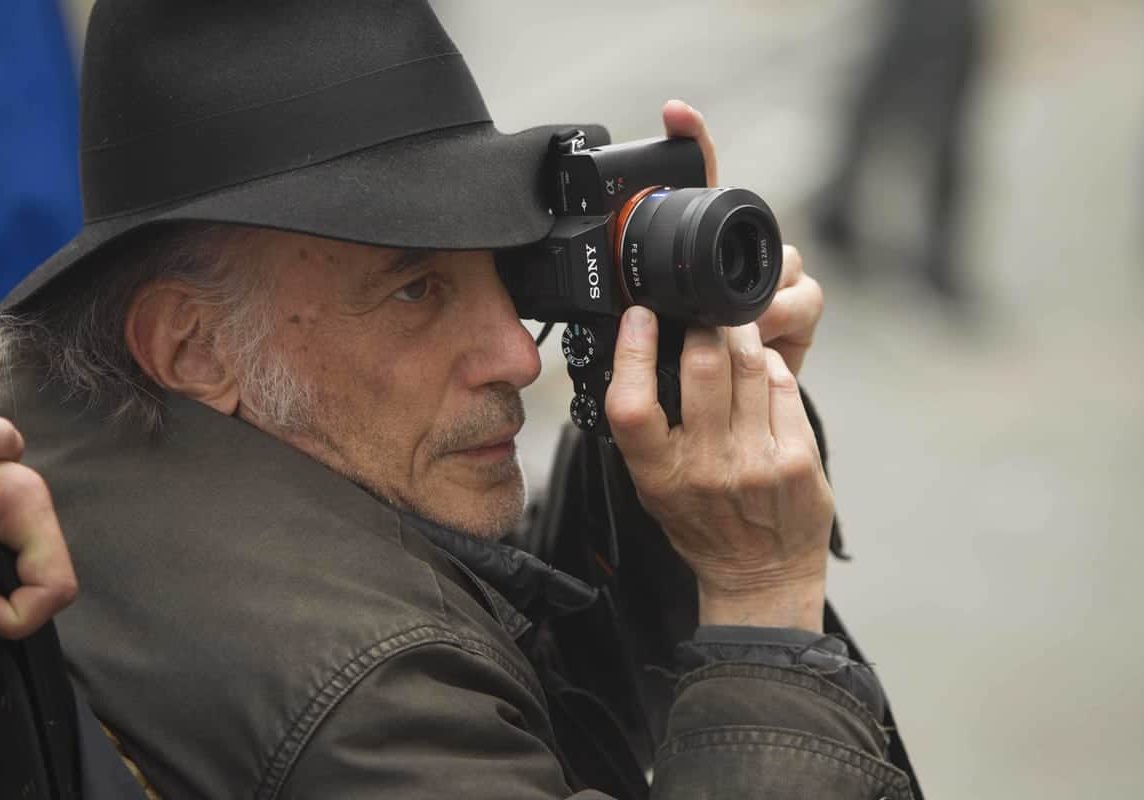

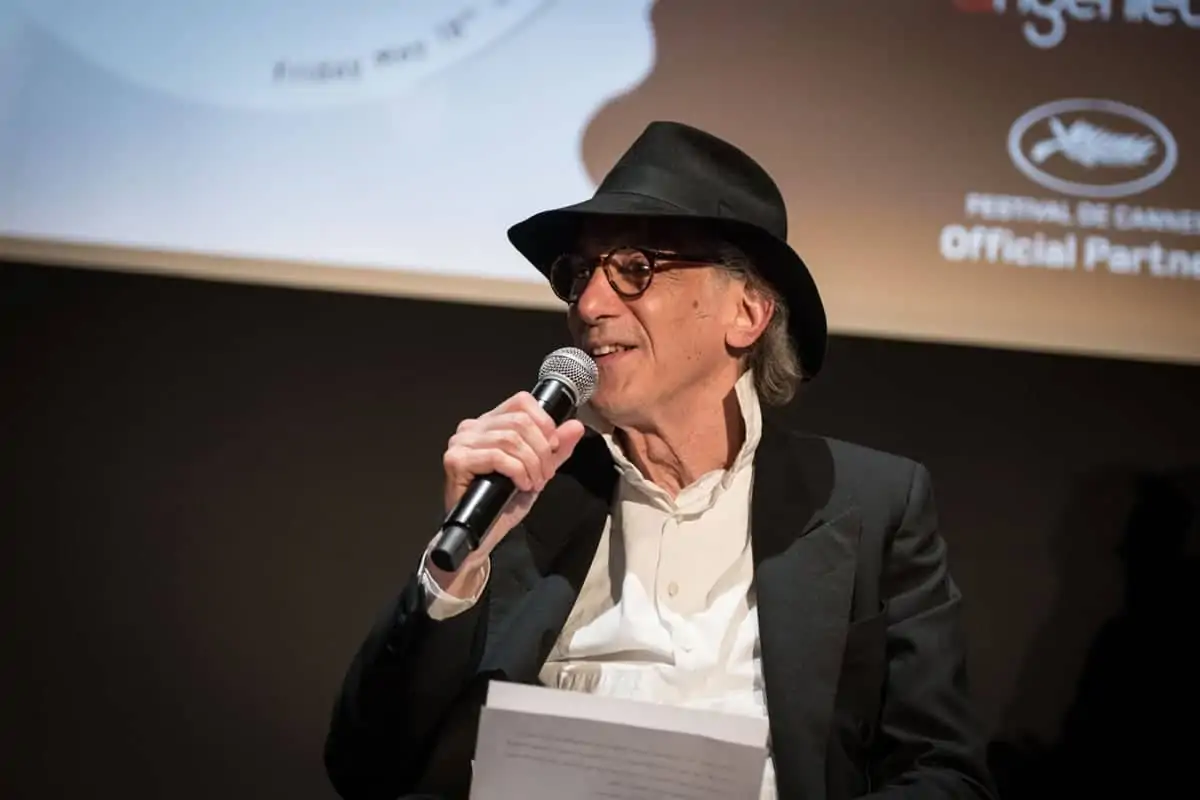

What does it mean to you to be honored with the Angénieux Award at the Cannes Film Festival? (above & below)

When you get an award like this, and it is certainly a great honor especially if I consider the other cinematographers who have received this award that I have the greatest respect for, like Philippe Rousselot, Roger A. Deakins, Peter Suschitzky, and Chris Doyle last year. Chris has my greatest respect, I love his spirit and his soul in his work. It always seems like this is a closure to your creative life but hopefully the spirit of discovery and problem solving doesn’t. I hope we only grow with our own experience and we learn through others.

As I got older with more experience, I learned that there’s more than one way to solve a problem creatively. The important thing is that we look inside and outside ourselves with new eyes. And yes, it is a lifetime of exploring, but knowing it’s in the journey and not the final destination.

What’s the next project you are working on?

I’m doing a project with Todd about the Velvet Underground and it’s one of the first documentaries he’s ever done. A lot of it is archival footage, but it’s also going back and interviewing a lot of the people around the art and music scene in the Seventies that came out of New York with the Velvet Underground.

Working on the film has become a way of revisiting my past, as I had even directed and shot a concert film with Lou Reed and John Cale called Songs for Grow Up for Channel Four in 1990. I knew Nico personally and worked with Lou on an early video, Berlin, so it’s kind of strange to look back and document something that I was on the peripheral of.

I am also working with a remarkable French artist, JR, who is an incredible inspiration with the socially conscious projects he creates, involving local communities in his art. The project is with the New York Film Festival for 2018.