Breaking Ground and Breaking Boundaries

Across The Pond / Mark London Williams

Breaking Ground and Breaking Boundaries

Across The Pond / Mark London Williams

Head Image: ASC President Kees van Oostrum and ARRI President and CEO Glenn Kennel preside over the groundbreaking ceremony for the ASC ARRI Educational Center (Lisa Muldowney - ignite)

If terms like “previs,” green screen” and “rendering” are all relatively new in the cinematographers’ lexicon since the days of “chicken coops” and “barn doors,” imagine what one of those DPs from yesteryear, working with sweltering lights, cable pullers and film loaders, would make of the term “virtual cinematographer”.

This is not to be confused with various maladies of the digital era that might also use the term - someone with a “virtual” partner or spouse, or living under a “virtual” President, etc. Rather, the term has found its way onto IMDB as an aspect of post-production. Or due to the ways that “pre” and “post” all merge now, simply into “production.”

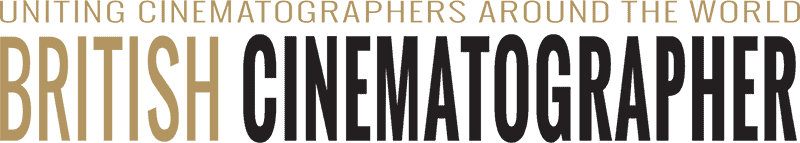

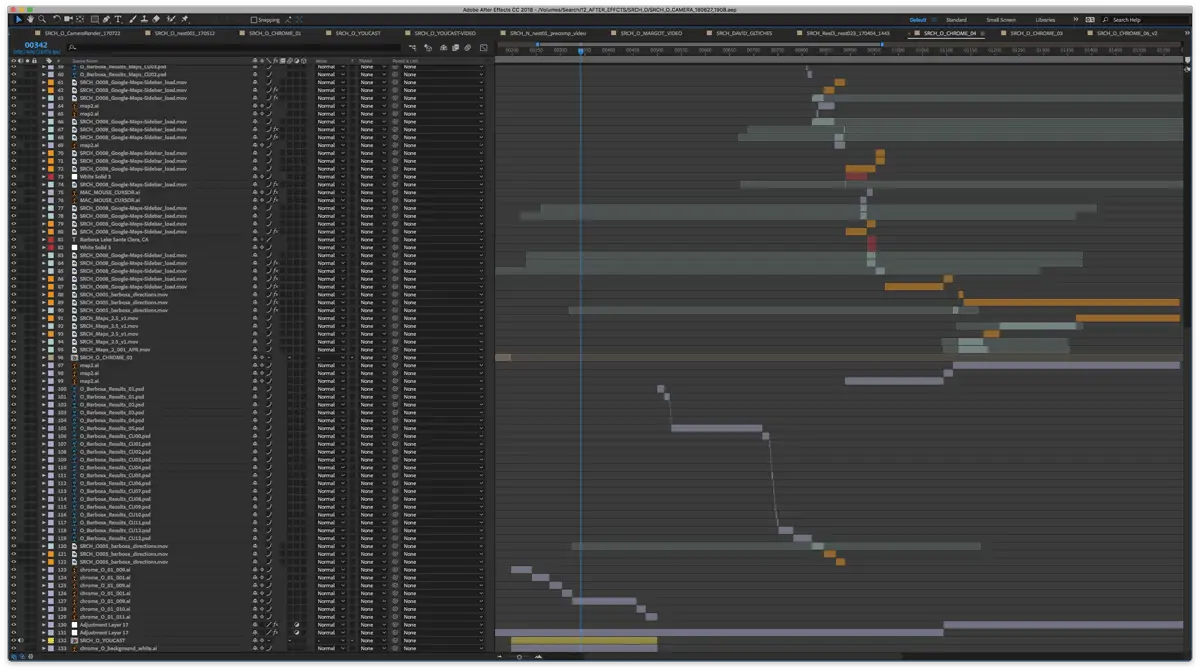

We were able to talk to two such virtual cinematographers, Nicholas D. Johnson and Will Merrick, who worked with DP Juan Sebastian Baron - and director Aneesh Chaganty - on the thriller Searching. The film is told from the POV, in a sense, of a missing 16 year old’s laptop, after her distraught father breaks into it - trying to sift through the digital detritus of her life for clues to her disappearance.

“This was definitely pretty unusual,” Merrick told us - since he’s also credited, along with Johnson, as an editor on the film. “How cinematic can a film told through a computer screen be?”

The question might be a bit rhetorical. The same production company had released the earlier Unfriended, Johnson noted, a fairly effective low budget film told in a series of chats gone horribly awry, as a shared secret begins to emerge online, but “the major difference there, is that was told entirely in real time. It’s pretty effective as a horror movie. But not particularly cinematic. We wanted to cut, we wanted to have fades, and reverse shots - all that stuff.”

![SEARCH_STILL01_John Cho_Photo Cred Sebastian Baron[2]-p1cln4ofpc15dvgjn1ju615kt1tj5 (1) Still from <em>Searching</em>. Credit: Sebastian Baron](https://britishcinematographer.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/SEARCH_STILL01_John-Cho_Photo-Cred-Sebastian-Baron2-p1cln4ofpc15dvgjn1ju615kt1tj5-1.webp)

Some of that “stuff” had been shot by Baron - “the live action elements - Facetime videos, news videos - he went out and shot all those. Now,” Johnson says, “imagine a computer that’s one big wide shot. To direct the audience’s attention we’re going to go in with an imaginary camera. That’s what sets this movie apart from the others.”

And yet, surprisingly they also consider their work an “analog” to the gonzo-themed animated film Rango, where “Roger Deakins was credited as a cinematographer (or consultant for some, depending where you look). He came in and worked on lighting and framing. On top of editing, we were in charge of framing.”

So framing within the frame, as it were, became part of their duties, and one of the reasons the producers wanted to credit them thusly. They found that they were using non-traditional tools in their (so far) non-traditional roles. While as editors, they were cutting on Adobe Premiere Pro, it was Adobe’s After Effects that got pressed into additional service.

They colorized a lot of Baron’s “live” footage, then “did a final macro-pass in DaVinci,” to add camera blur, vignettes (for that subtle direction within a frame or shot), etc. There could sometimes be up to “two hundred layers in a given comp.”

“It’s amazing what we could do in After Effects,” Johnson said, “given that it’s not a color correction program. A lot of our projects,” he adds, “took a very long time to load.”

“We built a technical workflow for this that was so specific that we’re not likely to use it again,” Merrick adds, “telling the most precise story you can and being kind of anal about it”

But one-of-a-kind workflows, and taking software into unchartered territories is precisely what Adobe wanted them to do. Indeed, it’s what Adobe would like everyone in the production and post-production world to do, as they made clear when opening their new Santa Monica offices - a kind of digital sandbox - for a press tour earlier this summer.

A look at Adobe's new Santa Monica office, and its press tour (Images: Peter Zakhary, Tilt Photo)

While they’ve worked with the likes of David Fincher, the Coen Bros. and James Cameron, and certainly acknowledge they’d love Premiere Pro to become an industry “default,” their Santa Monica facility isn’t really being promoted as a “genius bar,” but rather a “high-level concierge.”

Helping provide some of those upscale concierge services is Adobe’s Principle Strategic Development Manager, Mike Kanfer. Kanfer had worked at Digital Domain, among other post houses, on the VFX side, ultimately sharing an Oscar with Rob Legato, and others, for his work on Titanic.

And “sharing,” we might say, is part of the ethos around which this well-concierged sandbox was built. He recognizes the obligation for their facility - and software designs - to “play well with others.” Hence, Johnson and Merrick’s use of Blackmagic’s DaVinci Resolve as part of their mostly “After Effects” process finishing Searching.

“We can handle the metadata that comes in, or needs to go out,” Kanfer says, and such agnosticism - whether Blackmagic’s, Avid’s, or Adobe’s (or the files in a camera) - is increasingly the norm in the “cloudy” world of production and post.

"One-of-a-kind workflows, and taking software into unchartered territories, is precisely what Adobe wanted [Nicholas D] Johnson and [Will] Merrick to do, and what they would like everyone in the production and post-production world to do."

Such agnosticism was also on display at The Reel Thing, the annual conference held by AMIA - the Association of Moving Image Archivists - at the Academy’s Linwood Dunn theater, in the veritable heart of Hollywood. In this case, the “open source” aspects are not for projects currently in the pipeline, but for many done decades - sometimes a century - ago. Long before the word “pipeline” - let alone “digits” - would’ve been applied to film production.

The two-day, three-night symposium is also a great place to catch restored prints - we saw a magnificent new print of Billy Wilder’s The Apartment (shot in glorious black-and-white by Joseph LaShelle), though had to reluctantly miss screenings of revived copies of The Bicycle Thieves and George Pal’s War of the Worlds.

But now that we know we want to preserve movies (and TV shows) for the long haul - something they didn’t consider back in the days of von Stroheim’s Greed, for example - how can we protect all these digital assets for the future, even as the world of software packages, and the devices that run them, continue to change at seemingly a “60 fps” rate?

One solution being touted comes from the Academy itself - and it’s ACES. Literally, since those initials stand for the “Academy Color Encoding System,” whose mission is to “ensure a consistent color experience that preserves the filmmaker’s creative vision - from image capture through editing, VFX, mastering, public presentation, archiving and future remastering,”

The development of ACES continues to be open-sourced, but how can they guarantee today’s digits will be available for tomorrow’s remastering? Well, part of that is in initiatives like the “Academy Digital Source Master,” improvements to which went live online during the conference itself.

But ones and zeroes aren’t the only nuts and bolts here. Andy Maltz, of the Academy’s Science and Technology Council acknowledged there was a “trust factor” involved, too - that future software engineers (and users and archivists) would actively work to preserve and work for the “migration” of today’s “content” when it recedes into history.

That was in response to a question comparing those digits to film: We already know film can endure for a century - if it’s preserved right. We don’t yet quite have that “proof text” on the digital side: What will the retrieval mechanisms of the 2080s be like? Or the 2110s!? (Heck, will those components need extra cooling due to a super-heated climate?)

This came up at lunch with ASC President Kees van Oostrum, on the occasion of the ground-breaking for the new ASC ARRI Educational Center, on former parking lot space behind the august society’s “Clubhouse,” just east of Hollywood Boulevard. The new building will host educational and demonstration events, along with our colleagues at the ASC’s magazine. So far, no mention of “archival work” - except in the hands-on sense.

We chatted briefly with Kees about his last appearance here, where we discussed Vermeer and other master painters being, perhaps, born-too-soon DPs or photographers, using what media was available to them to control, be inspired by, and play with, light, in the centuries in which they lived.

He mentioned an uptick in the use of film in productions, and the need to let younger DPs know they at least have that option. There’s a reason so much re-housed glass is going on digital boxes, after all - people want their imagery to be more “Dutch canvas” and less “police interrogation room,” in terms of starkness.

![WP_20180828_12_03_21_Pro[1] ARRI hats all lined up ahead of the ASC groundbreaking ceremony](https://britishcinematographer.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/WP_20180828_12_03_21_Pro1.webp)

We talked about another conversation we’d had at Panavision Hollywood the day before - about which, much more next column - where young DPs were mustering out of film school having never loaded film, or shot on it, at all.

No one is questioning that the distribution networks will remain resolutely digital, nor is anyone saying that everything - or even most things - should be shot on film. But putting aside the aesthetics, what about considering it as an archival choice for the project’s original “image capture?”

And we already know, film and digits can “play together,” like all those post-production clouds can. This came up in one of The Reel Thing’s morning seminars called The Burden of 10k Dreams, which talked about mastering in… 10k!

One of the seminal pieces so translated was the late Les Blank’s Herzogian documentary, The Burden of Dreams - hence the title. But why would you need such a torrent of data? For those 8k wall-size public monitors that are coming? Or perhaps because there are still things to discover in the image.

HBO helped fund one such prototype mastering, in conjunction with Prime Focus, for the mid-‘90s film The Tuskegee Airmen. As Prime Focus’ Anthony Matt showed before and after clips, it turns out there was much fine grain detail - down to reflections on a pearl necklace in one medium shot - yet to be revealed.

Which means, even if we haven’t seen all that digits can do yet, perhaps we haven’t fully “seen” everything on the film side, either.

More to “see” and read next month!

Write us: @Tricksterink or AcrossthePond@gmail.com